Introduction

Long-term care is in a state of crisis, but you may have known that already. Nothing new. Before COVID-19 made its mark on the world and the industry, the tragedies within long-term care finally fell under scrutiny. At least here in Ontario. Due to the actions of a few bad actors, now tried and convicted, and the resulting investigation, the relatively new Ministry of Long Term Care (MLTC) issued the request for an investigation into the staffing situation within the industry. In the span of 6 months, despite the 1st wave of COVID-19, a 50-page document was produced. We have taken the numbers and compared them to the source where ambiguous and condensed them into a visual guide. In this 1st part, we will be looking at the state of Personal Support Workers (PSWs). Part 2 will explore the state of Nurses as outlined in this study into long-term care in Ontario.

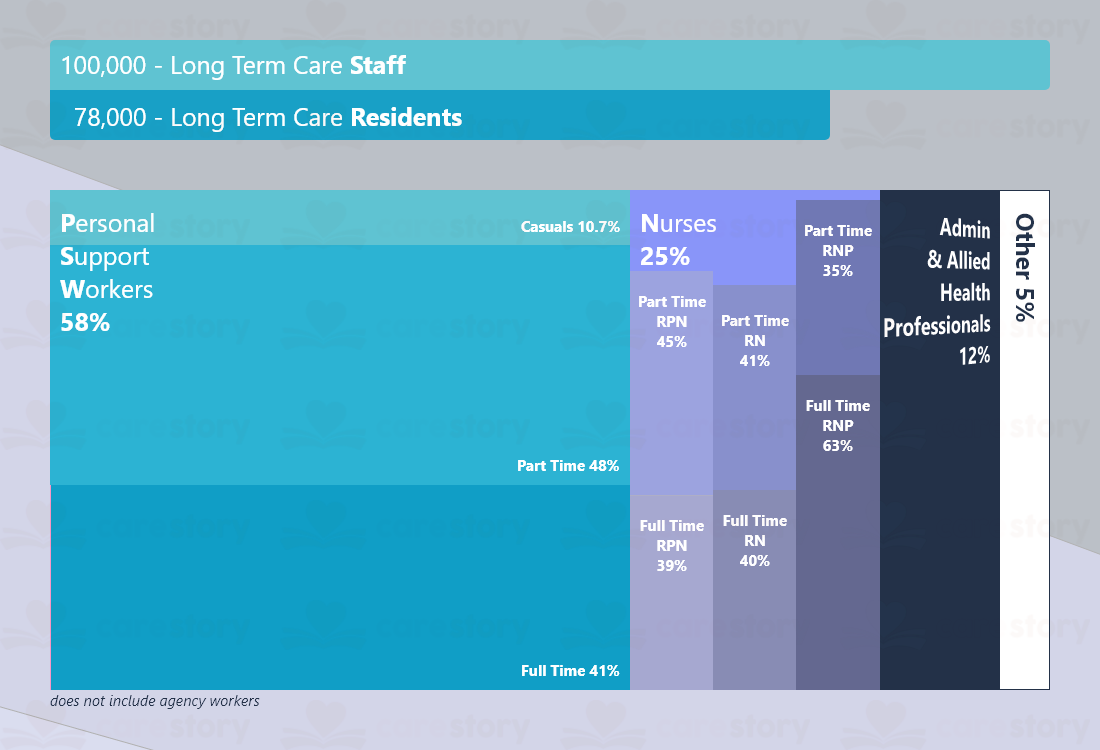

Staff Distribution

At first glance, the above data may seem promising, but it’s far from the truth. One staff member per resident may seem like a dream come true, everyone has one, and there are a few to spare. Where’s the problem? Why is everybody screaming that we need more PSWs? They make up 58% of the hired staff of a home?

Mental health and chronic conditions can’t wait 12-16 hours until a caregiver is back on shift. It can’t wait over the weekend or when a caregiver has to take time off. With less than half (PSWs, Practical Nurses, and Registered Nurses) working full time, you can be sure that 1 staff to 1 resident becomes 1 staff to 2 residents if we talk about 1 shift a day.

Despite being more than 1 hired staff per resident, despite there being more than 1 trained PSW in Ontario per resident in long-term care, residents still receive on average 2.3 hours of attention from a PSW in a 24h time period. This is on par because, when talking about long-term care PSW, it employs only half of all the PSWs in the province. Clearly, not the 1 to 1 days we are hoping for.

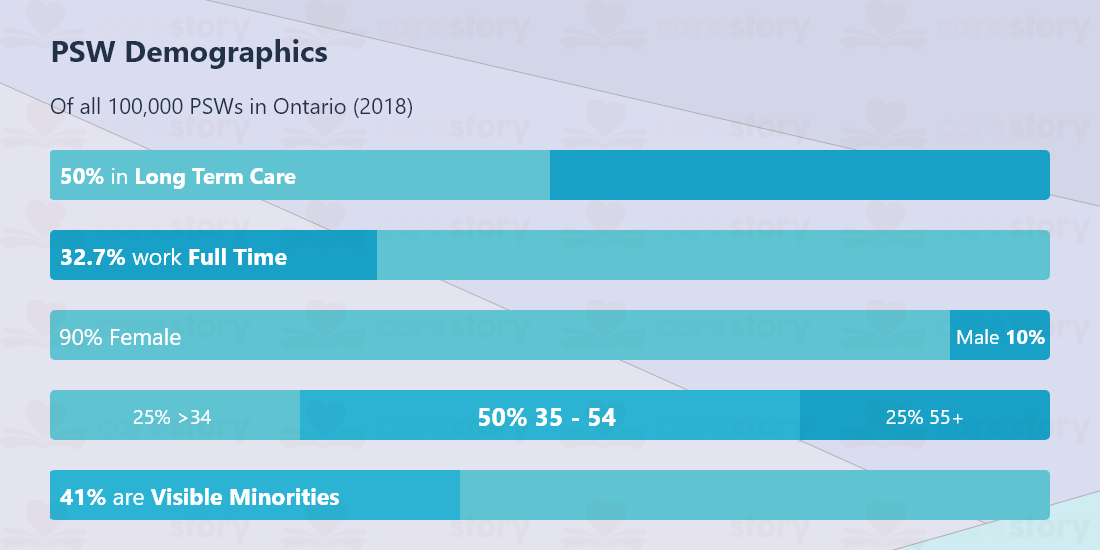

Demographics Unpacked

Although anecdotal, regarding demographics, many of the homes we work with also tell us that the first language of close to half of their caregivers is not English. This is not to say they lack fluency, but an indicator of them being 1st generation immigrants; this in part can be correlated with age and sex distribution. Healthcare and Education being female-dominated industries, both preferred choices of new immigrants who may lack the transferable work or educational experience, or Canadian accreditation may come at a higher cost than that of transition.

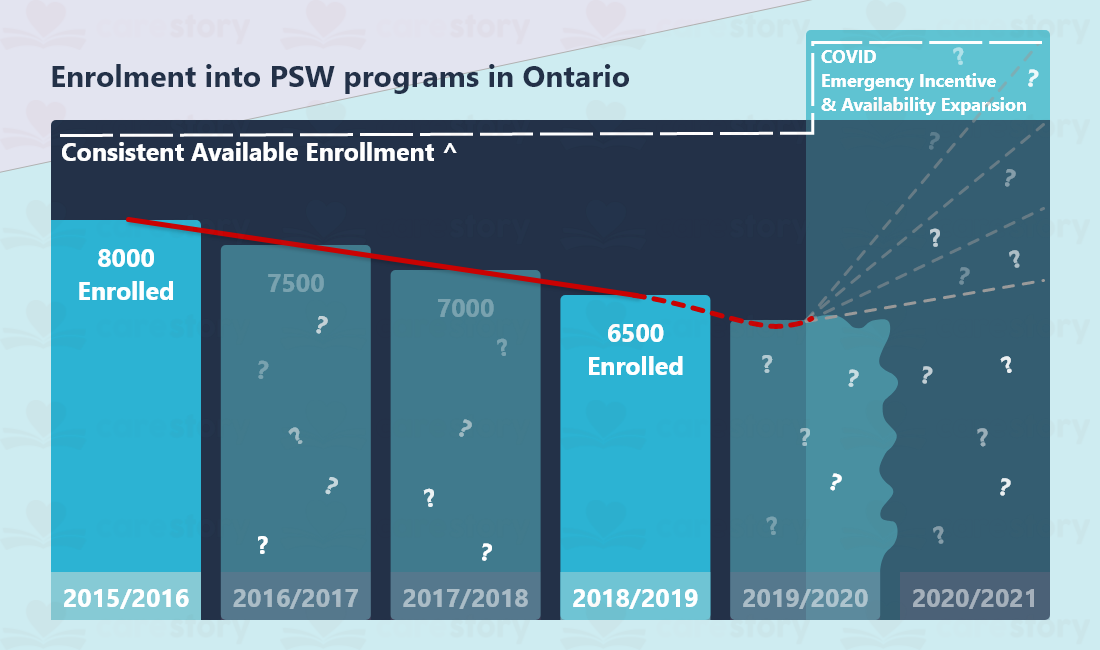

Enrollment

Although an attractive job for newcomers, and a position in high demand, there is not enough incentive to become a PSW. At the time of writing, we did not receive a number for the available enrollment positions across the province, but the long-term care study describes it as “consistent.” Across the years, a visible drop of students is visible from 8000 in 2016 to 6500 in 2019. Of note, the same document also mentions the industry losing on average 9000 PSWs/year as of 2011.

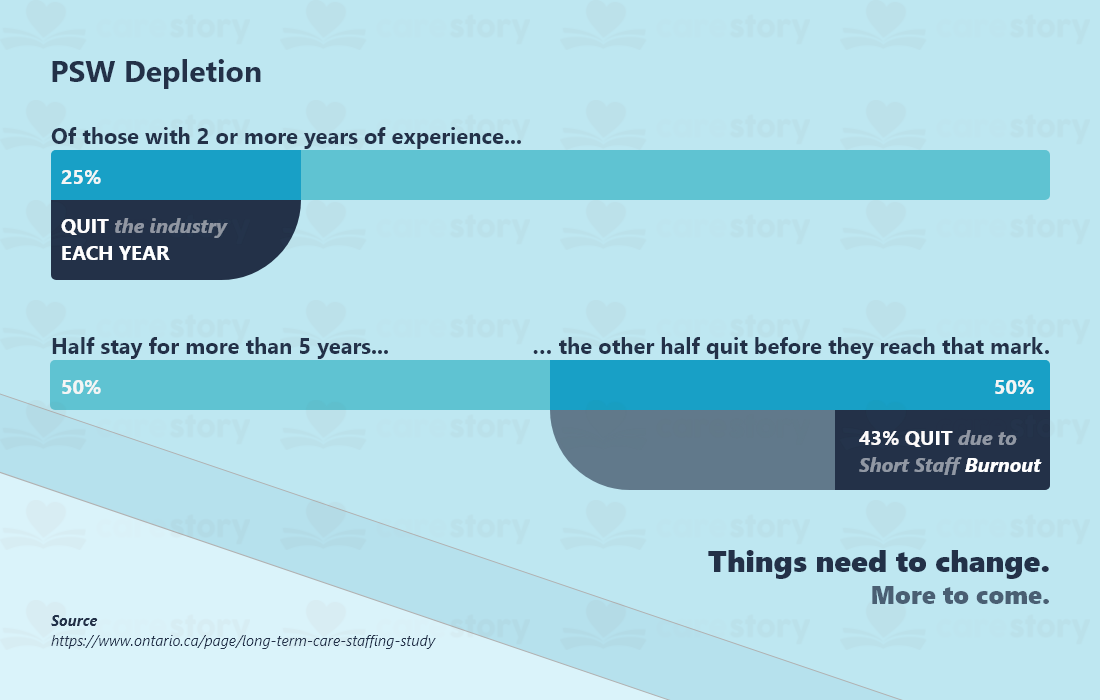

Drop out, burn out.

Caregiver job satisfaction is the leading cause of burnout and them fleeing the industry. The lack of attractive wages does not help the situation either.

Understandably, staffing can be the largest cost of a home. Hiring more people may mean that everyone gets fewer hours or a smaller hourly pay. It’s not fair.

Without a top-down reform, attractive salaries, and industry recognition, there are few options to go with. Among them is to invest in technologies that can better the lives of caregivers. Enhancing communication for everyone will result in a better environment to work in and better care outcomes. We’ve actually written about strategies a home can adopt to avoid staff burnout. Free online resources and working with as opposed to ‘around’ or ‘against’ the families is a great first step. You can read it here.

Download the infographic from here.

Lastly, if you wish to read the full study the infographic is based on, you can do so here.

Part 2 – Nurses coming in 2 weeks.